How to Get Fair Results from a Biased Coin

05 Jul 2015This is a test of org-babel.

Problem Formulation

Consider we have a biased coin, such that the probability of getting a head is \(P(H) = p\in(0,1)\) and the probability of getting a tail is \(P(T) = q = 1-p\), where \(p\) is unknown by us. However, different coin tosses are independent from each other.

Our goal is to generate a "fair" binary random variable \(X\), with distribution \(P(X = 0) = P(X=1) = 0.5\).

Von Neumann's Solution

One way to generate such a random variable is to:

- Toss the coin twice.

- If the result is HT, assign \(X = 0\). If the result is TH, assign \(X = 1\).

- If the result is either HH or TT, then discard the two coin tosses and go to step 1.

The probability of making an HH or TT for two tosses is

\begin{align} \label{eq:failprobability} P(HH) + P(TT) = p^2 + q^2. \end{align}Therefore, the probability of finally getting HT (and thus setting \(X = 0\)) is1

\begin{align} &P(HT) + \left(P(HH) + P(TT) \right)P(HT)\nonumber \\ &+ \left(P(HH) + P(TT) \right)^2P(HT) +\dots\nonumber\\ & = \frac{pq}{1-p^2-q^2} = \frac{1}{2}. \label{eq:zeroprobability} \end{align}Similar, the probability of \(X = 1\) is \(0.5\) and hence we get a fail result from a biased coin.

The expected number of coin tosses needed to generate \(X\) is

\begin{align} \label{eq:expectnum} \sum_{n=1}^\infty 2n(1-p^2-q^2)(p^2+q^2)^{n-1} = \frac{1}{pq}. \end{align}Below is a python script for the coin toss algorithm:

import random def flipcoin(p): if random.uniform(0,1) <= p: return 'H' else: return 'T' def check(toss): #return s, where n = 2^s*(2t+1) if toss == 'HT': return 0 elif toss == 'TH': return 1 else: return None X = None p = 0.5 print("Coin Toss Sequence: ", end = "") while X is None: toss = flipcoin(p) + flipcoin(p) print(toss, end = "") X = check(toss) print("\nX = " + str(X))

A More Efficient Algorithm

The above algorithm is not every efficient in the sense that it wastes some coin tosses. To see this, consider the sequence HHTT and TTHH. Notice that they both occur with probability \(p^2q^2\) and thus we can map HHTT to \(X = 0\) and TTHH to \(X = 1\). However, in the above algorithm, both of the sequences will be discarded.

To generalize this idea, we will define an \((n,m)\) sequence to be a coin toss sequence with \(n\) tosses and \(m\) heads. We know that all \((n,m)\) sequences will have the same probability \(p^m q^{n-m}\). Thus, if \(n\choose{m}\) is even, then we can map half of such sequences to \(0\) and the other half to \(1\). This will lead to a more efficient use of coin tosses.

However, some sequences may terminate early. For example, there are \(6\) possible \((4,2)\) sequences. However, the sequences HTHT is not possible since we will stop coin tossing when we see the first two coin tosses: HT. In fact, HHTT and TTHH are the only \(4\) toss sequences with \(2\) heads.

In order to take this early termination into account, let us define \(m(k)\) as the number of heads after $k$-th coin toss. Then the coin toss sequence of length \(n\) can be uniquely determined by \(m(1),\,m(2),\,\dots,\,m(n)\). Indeed, the $k$-th coin toss is H if \(m(k) - m(k-1) = 1\). It is T if \(m(k) -m(k-1) = 0\). 2

We will call a \((n,m)\) sequence of to be valid if it does not terminate before the $n$-th toss3. In other words, for all \(k < n\), \(k\choose{m(k)}\) is odd. Let us define \(f(n,m)\) to be the number of valid \((n,m)\) sequences.

\(f(n,m)\) is either \(0\), \(1\) or \(2\). Moreover, \(f(n,m)\) satisfies4:

- If \(f(n-1,m-1) = 1\) and \(f(n-1,m) = 1\), then \(f(n,m) = 2\).

- If \(f(n-1,m-1) + f(n-1,m)\) is odd, then \(f(n,m) = 1\).

- Otherwise \(f(n,m) = 0\).

The proof follows from the following facts:

- If a \((n,m)\) sequence is valid, then the first \(n-1\) tosses must be either a valid \((n-1,m-1)\) or a valid \((n-1,m)\) sequence.

- We will terminate our toss whenever \(f(n,m)\) is even.

We can us the following code to generate a table of \(f(n,m)\).

def table(N): fold = [1,] #f(0,0) = 1 print('1') for n in range(1, N+1): fnew = [1,] #f(n,0) is always 1 print('1', end=' ') for m in range(1, n): f = fold[m-1] % 2 + fold[m] % 2 #Apply Thm 1 fnew.append(f) print(str(f), end=' ') fnew.append(1) #f(n,n) is always 1 print('1') fold = fnew table(10)

1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 2 1 0 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 1

By Theorem 1, we know that if \(f(n,m) = 2\), then the last toss of the one valid \((n,m)\) sequence is H and the last toss of the other is T. Hence, our more efficient algorithm can be described as follows:

- If \(k\choose{m(k)}\) is even, then assign \(X = 0\) if the last toss is T. Assign \(X = 1\) if the last toss is H.

- If \(k\choose{m(k)}\) is odd, then toss another coin and update \(k\) and \(m(k)\).

The algorithm can be implemented in the following code:

import random def flipcoin(p): if random.uniform(0,1) <= p: return 'H' else: return 'T' def factor2(n): #return s, where n = 2^s*(2t+1) if n == 0: return 0 s = 0; while n % 2 == 0: s = s + 1 n = n / 2 return s p = 0.5 k = 0 m = 0 even = False print("Coin Toss Sequence: ", end = "") while even is False: toss = flipcoin(p) print(toss, end = "") k = k + 1 if toss == 'H': m = m + 1 X = 1 if factor2(k) - factor2(m) > 0: even = True else: X = 0 if factor2(k) - factor2(k-m) > 0: even = True print("\nX = " + str(X))

In the above code, we use the fact that

\begin{align} { k\choose{m} }= \frac{k}{k-m}{ {k-1}\choose{m} } = \frac{k}{m}{ {k-1}\choose{m-1} }. \end{align}How Efficient is Our Approach

We now compute the expected number of tosses needed for the algorithm to terminate. To this end, let us define a random variable \(L\) to be number of coin tosses when the algorithm terminates.

Notice that if \(n = 2^k\), then \(f(n,m)\) is all even except for \(f(n,0)\) and \(f(n,n)\). Therefore, our algorithm will not terminate only if the all \(n\) tosses are H or T. For a general \(n\), suppose we can decompose it as \[ n = 2^k + n_2 = n_1 + n_2, \] where \(0 \leq n_2 < n_1\). If \(n_1 > m > n_2\), then we know that the first \(n_1\) tosses contains at least \(m-n_2\) heads and \(n_1-m\) tails. Therefore, all such sequences will terminate at \(n_1\) and hence \(f(n,m) = 0\).

Following this observation, we can verify the following equality:

\begin{align} \label{eq:fdecompose} f(n,m) = \begin{cases} f(n-n_1,m)&\text{if }m \leq n_2\\ 0&\text{if }n_2 < m < n_1\\ f(n-n_1,m-n_1)&\text{if }n_1 \leq m\\ \end{cases}. \end{align}Now let us write \(n\) and \(m\) in binary form. We will say \(n \triangleright m\) if every binary bit of \(n\) is greater than the corresponding binary bit of \(m\). Notice that \(\triangleright\) is a partial order on \(\mathbb N\). For example, \(9\) is \(1010\) and \(4\) is \(100\) in binary. Therefore, \(9\ntriangleright 4\) since the third bit of \(9\) is \(0\) while the third bit of \(4\) is \(1\). If we apply our formulate \eqref{eq:fdecompose} iteratively, we know that \(f(n,m) = 1\) if and only if \(n\triangleright m\). For our example, one can check that \({9\choose 4} = 126\) and thus \(f(n,m)\) is either \(0\) or \(2\).

Now if \(n\triangleright m\), there is only one valid \((n,m)\) sequence and the probability of this sequence is \(p^mq^{n-m}\). If we list all \(m \triangleleft n\) and add the probability together, we know that

\begin{align} \label{eq:lformula} P(L > n) = \prod_{k_i} \left(p^{2^{k_i}} + q^{2^{k_i}}\right), \end{align}where we assume \(n = 2^{k_1} + 2^{k_2} + \dots + 2^{k_l}\) and \(0\leq k_1 < k_2 < \dots < k_l\). For example, the valid sequences of length \(9\) can only have \(0\), \(1\), \(8\), \(9\) heads. Thus, the probability of having these sequences are \[ P(L > 9) = p^9 + q^9 + p^1q^8 + p^8 q^1 = (p+q)(p^8+q^8). \]

Since \(L\) is a positive integer, we have the following equality:

\begin{align} \label{eq:expectationtosum} \mathbb E L = \sum_{n=0}^\infty n P (L = n) = \sum_{n=0}^\infty P(L > n). \end{align}Now if we consider a partial sum from \(0\) to \(3\), we have

\begin{align*} \sum_{n=0}^3 P(L > n) &= 1 + (p+q) + (p^2+q^2) + (p+q)(p^2+q^2) \\ & = (1+p+q)(1+p^2+q^2). \end{align*}We can easily generalize this result to the partial sum from \(0\) to \(2^k-1\)

\begin{align} \sum_{n=0}^{2^k-1} P(L > n) =\prod_{i=0}^{k-1} (1+p^{2^i}+q^{2^i}). \end{align}Now take the limit on both sides, we get the expected number of coin tosses:

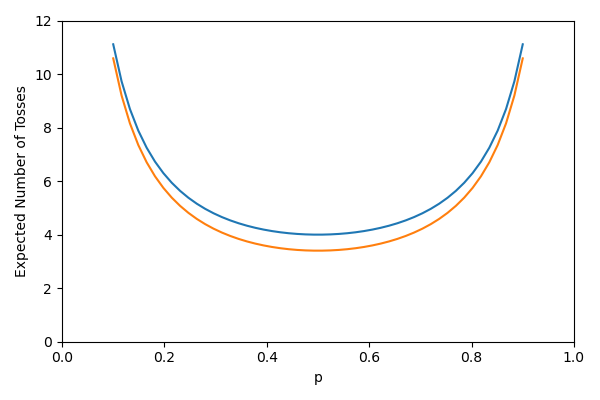

\begin{align} \label{eq:expectedcointosses} \mathbb E L = \prod_{i=0}^\infty (1+p^{2^i}+q^{2^i}). \end{align}The following python code compute the expect number of coin tosses for the Von Neumann's method (blue line) and our more efficient method (green line)

import matplotlib import matplotlib.pyplot as plt import seaborn as sns # for the sake of appreances import numpy as np p = np.linspace(0.1, 0.9) q = 1 - p # expected number of tosses for Von Neumann's algorithm l1 = 1/(p*q) i = 0 p2i = p #p^{2^i} q2i = q #q^{2^i} l2 = 1 + p2i + q2i for i in range(1, 10): p2i = p2i ** 2 q2i = q2i ** 2 l2 = l2 * (1 + p2i + q2i) fig=plt.figure(figsize=(6,4)) plt.axis([0, 1, 0, 12]) plt.plot(p, l1) plt.plot(p, l2) plt.xlabel('p') plt.ylabel('Expected Number of Tosses') fig.tight_layout() plt.savefig('../../public/expected-toss.png') return '../../public/expected-toss.png' # return the filename to org-mode

Can we be more efficient?

The answer is yes. Let us slightly change our algorithm to:

- If \(k\choose{m(k)}\) is even, then assign \(X = 0\) if the \(m(k-1)\) is odd. Assign \(X = 1\) if \(m(k-1)\) is even.

- If \(k\choose{m(k)}\) is odd, then toss another coin and update \(k\) and \(m(k)\).

The assignment table for the slightly modified algorithm is

| Toss | HT | TH | HHHT | HHTH | HHTT | TTHH | TTHT | TTTH |

| X | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Notice that HHTH and HHTT are both assigned to \(1\). Hence, we can terminate when we get HHT since we know that no matter what we get for the fourth toss, we will terminate the process and \(X\) will be \(1\).

This paper is for anyone who is interested in more details on this topic.